This conversion account of a Jewish atheist and avowed detractor of the Catholic Church provides great hope to many who feel helpless in view of family members and friends who seem to have little or no faith at all. Even the most hardened of hearts can be converted through the intervention of our Mother. Perseverance in prayer to Mary brings about astounding miracles, as happened in the life of Alfonse Ratisbonne who, himself, was surprisingly caught off guard by wearing the Miraculous Medal, simply as a mockery, to placate the request of an acquaintance concerned for his salvation.

On January 20th, 1842, a twenty-seven year old, handsome young Jewish man strode into the tiny, poor Church of San Andrea Delle Fratte, in Rome, with an expression of distaste. There was no art inside, worth his attention. This is certainly a very ugly church, his glance told his new Catholic friend, Baron Theodore de Bussieres, as he glanced around the building. His eyes were cold and indifferent.

Baron Theodore de Bussieres had tried hard in the last several days to convert this newcomer, Alphonse Ratisbonne, to Catholicism, while he guided him around Rome. However, the tourist mocked his beliefs, blasphemed his God without compunction, and laughed at all his efforts, leaving him unable “to indulge the feeblest hope that I had, in any degree, shaken his convictions.”

Seeing the look on his face now certainly did not make Baron de Bussieres feel any better. All that morning, Ratisbonne had been involved in the idlest chatter with friends, proving to De Bussieres that he had no serious preoccupation of mind at all. De Bussieres could see plainly that all his arguments made no difference.

Alphonse Ratisbonne had hated the Catholic Church since he was young. When Alphonse’s brother, Theodore Ratisbonne, converted to Catholicism, this wounded their entire family, and then Theodore went on to become a priest and preach in the same city where their family lived. To Alphonse, all this was an outrage!

So when Ratisbonne’s new friend, Baron Theodore de Bussieres, tried to convert him to Catholicism with arguments, he didn’t even bother to refute him. He couldn’t take him that seriously; he preferred just to make jokes out of everything De Bussieres said about religion.

Ratisbonne glanced around San Andrea Delle Fratte, at the funeral preparations being made around them. He asked who this was for. “For a friend I have just lost, and whom I loved very much,” Baron de Bussieres said. “De Laferronnays. His sudden death is the cause of the depression of spirits you may have observed in me, the last day or two.”

Ratisbonne had noticed De Bussieres’ dejected spirit. However, he didn’t know Count De Laferronnays at all, so he wrote later that he only felt “that vague sorrow one always feels at hearing of a sudden death.”

De Bussieres needed to arrange for a gallery to be set apart for De Laferronnays’ family, in preparation for the funeral. “I shall not tax your patience long,” he said. “I shall not be away more than a few minutes.” Afterward, they would take their intended stroll together. De Bussieres went into the convent to conduct his business.

Ratisbonne began to walk around the nave, and De Bussieres left him to wait on the epistle side, to the right of a small enclosure that was to receive the coffin. All seemed quite normal around them; neither gentleman had the slightest notion that anything extraordinary was about to occur.

Just a few days before, Alphonse’s attitudes toward Catholicism did make a serious shift, but in the opposite direction from that which De Bussieres hoped. The occasion was Ratisbonne’s visit to the Roman Ghetto. Ratisbonne walked across the cracked, muddy Ghetto streets, along narrow lanes that ran between tall, dilapidated buildings. The streets were full of the Jewish poor. The cramped conditions and abject poverty they endured were crushing. Ratisbonne felt surrounded on all sides. His family raised him with a keen sense of social justice. After he obtained a diploma in the study of law, he decided to spend his life serving the Jewish people’s material needs. Now, as he looked around him in horror, Ratisbonne’s pity for the Jews and fury against Catholicism intensified to an incredible degree.

Where, he asked, bitterly, is that Roman charity of which so much is said? How, he demanded, could a whole nation deserve “to be the victims of such barbarous treatment and such endless prejudices, simply for having killed one man eighteen hundred years ago?” He wrote later that after his visit to the Ghetto, he “never felt so fierce a hatred toward Christianity.”

Then, only a few days after his experience, his feelings remained completely unchanged as he waited for his friend to emerge from the convent.

When De Bussieres walked back into the little, almost empty church, ten to twelve minutes later, he glanced around with uncertainty. He couldn’t see his friend anywhere. Then he caught sight of him… kneeling in front of the chapel of St. Michael the Archangel.

Up to this point in his life, and for the most part, Alphonse Ratisbonne had believed in no religion at all. “I was a Jew by profession,” he would say later, “and that was all, for I did not even believe in God. I never opened a religious book, and neither in my uncle’s house nor in those of my brothers and sisters was there the slightest observance of the injunctions of Judaism.”

After all he had seen and heard from Ratisbonne over the last several days, De Bussieres was stunned to see him kneeling in a Catholic church. De Bussieres quietly walked up to the kneeling figure and touched him gently. Ratisbonne did not make any movement. De Bussieres had to touch him two or three more times before he made any response. At last, the young man raised his face toward De Bussieres, his cheeks streaked with tears. He clasped his hands together and said of Laferronnays, “How this gentleman prayed for me!”

De Bussieres was utterly astonished. He had asked the distinguished politician and devout Catholic, Count de Laferronnays, to pray for Ratisbonne’s conversion just hours before the man’s unexpected death. But De Bussieres never told Ratisbonne a word about it.

He lifted Ratisbonne to his feet and half carried him out of the church. Just as the little children-seers of Fatima, three quarters of a century later, would find themselves physically weakened after a close encounter with the supernatural, Ratisbonne was so overwhelmed that he initially could hardly make his limbs move.

De Bussieres asked Ratisbonne what was the matter, but his friend could not answer. De Bussieres tried again, this time simply asking where he wished to go. “Lead me where you please,” he replied. “After what I have seen, I obey.”

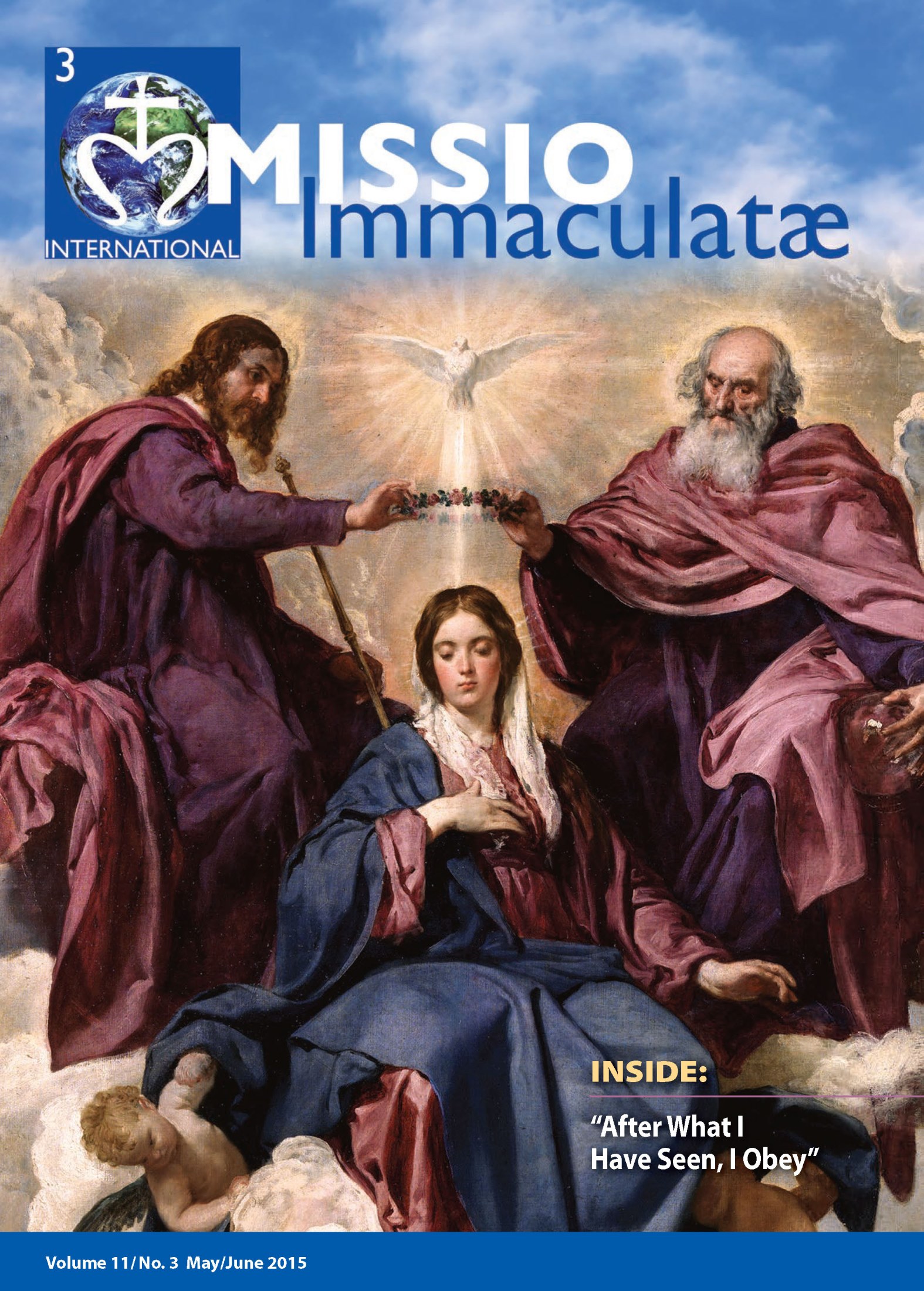

Eleven years earlier, on November 27, 1830, the professed sisters and novices of the Sisters of Charity, a religious order founded by St. Vincent de Paul, were gathered in their chapel, meditating in silence. Suddenly, in the stillness, one of the novices, twenty-four year old Catherine Labouré, heard the rustling of a silk gown. She turned toward the sound and her eyes widened. The darkness of the chapel disintegrated and brilliant light flooded the room where the sisters were praying.

“I saw the Blessed Virgin,” she would later write. “She was of medium height, and clothed all in white. Her dress was of the whiteness of the dawn… A white veil covered her head and fell on either side to her feet… Her face was sufficiently exposed, indeed exposed very well, and so beautiful that it seems to me impossible to express her ravishing beauty.” Later on in her description, she would come back again to the face, as though wanting to pass this treasured sight on in writing. However, she could only helplessly repeat, “Her face was of such beauty that I could not describe it.”

The Virgin had three rings set with gems on each finger; and dazzling rays of light shone down from these rings upon the earth and upon each individual soul, both of which were represented together as a golden globe under her feet. A voice spoke to Catherine. “These are the symbols of the graces I shed upon those who ask for them.” The words cast light into the girl’s soul, making her understand clearly that it was very right to pray to the Blessed Virgin, that she was lavishly generous to those who prayed to her, how magnificent were the graces she gave to all who asked, and what joy she had in giving them.

The voice speaking to Catherine went on, “The gems from which rays do not fall are the graces for which souls forget to ask.” A frame of oval shape, bearing letters of gold, appeared around the Blessed Virgin, which read: “O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to thee.” Later, on the reverse side of the frame, Catherine saw a large M penetrated by a bar and mounted with a cross. Beneath the M were the Hearts of Jesus and Mary. The Heart of Jesus was surrounded by a crown of thorns, and the Heart of Mary was pierced through by a sword.

Catherine heard the voice say, “Have a medal struck after this model. All who wear it will receive great graces; they should wear it around the neck. Graces will abound for those who wear it with confidence.” Soon, the golden ball under the Virgin’s feet was completely consumed by the brilliance of glorious beams of light bursting from every direction. The Virgin’s hands turned out and her arms bent down as though crushed under the great weight of divine treasures she had obtained for souls.

Catherine did everything in her power to keep her visions secret, hiding them from everyone except her spiritual director, Father Aladel.

The medal requested by the Virgin, initially named the Medal of the Immaculate Conception, was cast in 1832 and widely spread about. Soon, however, everyone was calling it “the Miraculous Medal,” because miracles were occurring in so many places where it had been distributed.

The signs were so great that even Pope Gregory XVI would eventually ask to meet the unknown, hidden sister who saw the vision and started to promote the medal. Sister Catherine’s spiritual director asked her if she would see the pope, but she keenly felt that she should remain hidden from everyone. She declined to meet him. Pope Gregory decided not to insist, though he had the authority to do so, and the visionary’s identity was allowed to remain a complete secret, even from the pope. The medal and its reputation continued to spread like wildfire. Thousands of miracles were being reported.

Baron De Bussieres happened to have one of the medals in his possession on that fateful January 15, when Alphonse Ratisbonne came to his door.

Ratisbonne had met Baron Theodore De Bussieres only once before, and he didn’t like him. He regarded him as an enthusiast, “in the ill-natured sense of the word,” he writes. Though De Bussieres tried to befriend him, Ratisbonne refused to treat him with anything other than “the cold civility of a well-bred man.”

As he planned to depart from Rome in the early morning of the 17th, Ratisbonne felt it was only polite to leave his calling card with his old schoolfellow, Gustave De Bussieres, as a farewell. When he found Gustave wasn’t at home, he went on to his brother’s house, planning to drop off the card and leave quickly.

He knocked, with no intention of going inside. An Italian servant opened the door, and, misunderstanding him, led him into the drawing room. Ratisbonne was extremely annoyed, but he hid this as best he could, beneath a reserved smile. He took a chair near Mme. De Bussieres, who was sitting beside two daughters. Theodore De Bussieres was also there to greet him.

“As I came down from the capitol, a melancholy spectacle rekindled all my hatred of Catholicism,” he recounted to De Bussieres. “I passed through the Ghetto, and as I beheld the misery and degradation of the Jews, I said to myself that it was a loftier thing to be on the side of the oppressed than on that of the oppressors.”

De Bussieres tried eagerly to prove to him that Catholicism was actually a grand religion and entirely true. Ratisbonne only smirked at him and began to insult his beliefs. I was born a Jew and a Jew I will die, Ratisbonne told him.

Abruptly, an idea occurred to Baron De Bussieres. He asked, “Since you detest superstition and profess yourself so very liberal about doctrine—since you are so enlightened—have you the courage to submit yourself to a very simple and innocent test?”

“What test?” Ratisbonne asked.

“Only to wear a little something I will give you,” De Bussieres said. “Look, it is a medal of the Blessed Virgin.” He held up a Miraculous Medal to him.

At the sight of it, Ratisbonne sunk back into his chair with a gesture of indignation and amazement. What a bizarre, puerile proposal!

“It seems very ridiculous,” De Bussieres acknowledged, “does it not? But I assure you I attach great value and efficacy to this little medal. From your point of view it must be a matter of perfect indifference, whereas it would give me the very greatest pleasure.”

Ratisbonne burst into laughter. “Oh, I will not refuse you. I shall at least show you that people have no right to accuse us Jews of obstinate and insurmountable prejudice. Besides, you are furnishing me with a charming chapter for my notes and impressions of my travels.”

He saw a childlike pleasure in De Bussieres’ face over this victory, and the baron was quick to take further advantage. “Now you must perfect the test,” De Bussieres told him. “You must say every night and morning the Memorare, a very short and very efficacious prayer which St. Bernard addressed to the Blessed Virgin Mary.”

De Bussieres refused to take no for an answer. He “combated his repeated refusals with the energy of desperation.” He said that refusing to recite the prayer made the test useless, and Ratisbonne’s refusal proved that Jews really were just as willfully obstinate as many claimed.

At last, worn down by De Bussieres’ ridiculous impertinence and not wishing to attach too much importance to this whole affair, Ratisbonne said, “Well, then, I promise to say this prayer. If it does me no good, it cannot do me any harm.”

Remember, oh most gracious Virgin Mary, that never was it known that anyone who fled to thy protection, implored thy help, or sought thy intercession, was left unaided. Inspired by this confidence, I fly unto thee, O Virgin of virgins, my Mother; to thee do I come, before thee I stand, sinful and sorrowful. Oh Mother of the Word Incarnate, despise not my petitions, but hear and answer me.

Ratisbonne found himself unable to stop praying these words. Not just once in the morning and once in the night, but all the time, “just as we unconsciously hum a tune which has struck our fancy.”

The next morning, Ratisbonne came to visit De Bussieres and said, “Well, I hope you have forgotten your dreams of yesterday,” referring to his conviction that he would one day convert. “I have come to say goodbye to you; I am off tonight.”

“My dreams!” De Bussieres replied. “The thoughts you are pleased to call dreams occupy me more than ever; and as to your going away, we will not speak of that, for you absolutely must put it off for a week.”

Later, Ratisbonne would write, “I was induced, incomprehensibly, to prolong my stay in Rome. I granted to the urgency of a man I hardly knew what I had obstinately refused to my most intimate friends.” He had originally come to the city contrary to his own declarations and plans. He could not understand why he allowed De Bussieres to pressure him into staying even longer.

Ratisbonne decided to let De Bussieres become his guide, showing him around Rome. All the while, Ratisbonne could not stop reciting the Memorare in his head, over and over again. “I kept muttering to myself, though with great impatience, that everlasting, importunate invocation of St. Bernard.”

In the middle of the night, Ratisbonne woke up and found himself facing a large black cross, without the figure of Christ on it. No matter where he turned or how he moved in his bed, the cross remained directly in front of his eyes. He would later say, “I made incredible efforts to drive away this figure, but they were all fruitless.” Eventually, he managed to fall asleep, and in the morning he shrugged off the strange experience and thought no more about it. Only later would he realize it was the same cross that was on the back of the medal he was wearing.

The next day, waiting for De Bussieres to conclude his business, Ratisbonne looked around the Church of San Andrea delle Fratte, without any definite thought or purpose, ready to wile away the extra time.

Suddenly, out of nowhere, he saw a black dog leap at him. But it vanished… it was as if he had been shielded from it. Then, the whole church around him disappeared. He writes, “I saw nothing further. Or rather, O my God, I saw only one object!”

He found himself looking directly at the Queen of Heaven, in all the splendor of her beauty. It was impossible for him to bear the glory of that radiant sight, and his eyes immediately fell. However, he wanted so badly to look at this Jewess again that he kept trying to raise his eyes three times more.

If anyone knew, understood and cared about the suffering of Ratisbonne’s people—her people—she did. And she wanted Ratisbonne to serve the suffering Jews in her place.

The glory of her beauty was so great that Ratisbonne could not raise his eyes any higher than her hands. Yet in these hands, he saw expressed all the secrets of divine pity. Ratisbonne tried to write of it later, and even as Catherine of Labouré could not describe the heavenly woman’s face, he found himself completely undone in the attempt.

And how should I speak of it? No words of man can even attempt to utter the unutterable. All description, however sublime, must be only a degradation of the ineffable reality.

I lay prostrate, my heart completely absorbed and lost, when De Bussieres recalled me to life. I could not answer his questions, but I grasped my medal and kissed the image of the Virgin, radiant with grace. It was indeed her very self.

I knew that De Laferronnays had prayed for me. I cannot tell how I knew it, any more than I can account for the truths of which I had suddenly gained both the knowledge and the belief. All I can say is that at the moment when the Blessed Virgin made a sign of her hand, the veil fell from my eyes; not one veil only, but all the veils that were wrapped around me disappeared, just as snow melts beneath the rays of the sun.

I came out of a tomb, out of an abyss, and I was living, perfectly, energetically living.

Lead me where you please. After what I have seen, I obey.

De Bussieres was staring at his friend, half holding him off the ground. He urged him to explain himself, but he could not. But Ratisbonne reached into his shirt and pulled out the Miraculous Medal hanging from around his neck. He lifted it to his lips and kissed it, tenderly.

De Bussieres took him back to his apartment and couldn’t resist asking him more questions about what happened. Ratisbonne suddenly burst out, “How good is the Lord! What a fullness of grace and happiness! How pitiable the lot of those who know him not!” Tears streamed down Ratisbonne’s face at the thought of heretics and unbelievers.

“Take me to a confessor,” he begged De Bussieres. When could he receive baptism? He could not live without it! He yearned for the blessedness of the martyrs whose sufferings he saw depicted on the walls of San Stefano Rotundo as he walked by. Those horrifying sights previously disgusted him.

De Bussieres desperately wanted to know the whole truth; what had happened? Ratisbonne said he would not explain until he received permission from a priest: “What I have to say is something I can say only on my knees.”

Ratisbonne was desperate with longing to be baptized.

De Bussieres guided his overwhelmed friend to the huge, gloriously crafted Church of Gesù, the “Mother Church” of the Society of Jesus. The building’s dome was covered with radiantly colorful images of saints and angels, in bright hues of red, gold and blue. There were gold and marble walls, pillars and images. Sculptures adorned the walls, but after what Ratisbonne had just been through, all of this beautiful imagery representing the heavenly could only be nothing. What he experienced surpassed it as the sun surpasses a spark.

De Bussieres guided him up to Fr. Villefort, a Jesuit priest. Only that very morning, Ratisbonne loathed the Jesuits more than anything, but here he was now, gladly approaching a priest in the Jesuit Mother House. His feelings of hatred toward them were gone, forever.

Fr. Villefort asked Mr. Ratisbonne to explain himself. Ratisbonne snatched the Miraculous Medal out from under his shirt, kissed it and showed it to him and De Bussieres.

“I have seen her!” he cried.

Fr. Villefort and De Bussieres waited for a moment, and Ratisbonne soon calmed down. Then, he made his statement, for them.

“I had been in the church only a few moments when I was suddenly seized with a profound agitation of mind. The building disappeared from before me. One single chapel had, so to speak, gathered and concentrated all the light. In the midst of the radiance, I saw standing on the altar, tall, clothed in splendor, full of majesty and sweetness, the Virgin Mary, just as she appears on my medal.”

Fr. Villefort and De Bussieres found themselves listening with awe.

Ratisbonne went on, “an irresistible force drew me towards her. She made a sign with her hand that I should kneel; and then she seemed to say, ‘That will do.’ She spoke not a word, but I understood all.”

The light that struck Ratisbonne in those moments had illuminated his mind to doctrines of faith, such as original sin, which he never even heard about before. The reason he so longed for Baptism was that he wanted badly to have his stain of original sin washed away. In the moments after his vision, he wept, seeing what a terrible fate he had been rescued from, but also because he saw all the rest of the family he so loved still stained with original sin.

He would later be asked how he gained such knowledge in matters of the Faith. Ratisbonne writes, “All I know is that when I entered that church I was profoundly ignorant of everything, and when I came out, I saw everything clearly and distinctly. I was like a man suddenly roused from slumber, or rather like a man born blind, whose eyes are suddenly opened. He sees indeed, but he can give no definition of the light in which he beholds the objects around him.”

After their conversation with Fr. Villefort, Ratisbonne wanted to go immediately to give thanks to God. He and De Bussieres went first to Santa Maria Maggiore, the basilica favored by the Blessed Virgin, and then to St. Peter’s basilica. “How good it is to be here!” Ratisbonne told De Bussieres. “It is earth no longer; it is the vestibule of heaven.”

However, when they approached the altar where the Blessed Sacrament was reposed, De Bussieres found it necessary to take Ratisbonne away. Ratisbonne was utterly overwhelmed by the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist; he couldn’t bear to stand in the presence of Infinite Purity, while stained by original sin. Ratisbonne fled to the Blessed Virgin’s chapel and said, “Here, I can have no fear. I feel myself under the protection of an unlimited mercy.”

Thinking about his vision of the Virgin, Ratisbonne cried out, “O my God! I who only a half hour before was still blaspheming! I who felt such a deadly hatred of the Catholic religion! And all who know me know well enough that, humanly speaking, I have the strongest reasons for remaining a Jew. My family is Jewish; my betrothed is Jewish; my uncle is a Jew. In becoming a Catholic, I sacrifice all my interests and all my hopes I have on Earth; and yet I am not mad. Everyone knows that I am not mad, that I have never been mad. Surely they must receive my testimony.”

However, he soon realized that even if he had a right to be believed, they might still refuse. Increasingly afraid that his family would ridicule him, he begged Fr. Villefort to keep his vision a secret. He wanted to slip away to a Trappist monastery and disappear without facing the world’s cruelty. The Jesuit Fathers told him that drinking of Christ’s bitter chalice, which He drained at Calvary, was what it means to be a real Christian. They told him that Christ predicted that His disciples would suffer.

Ratisbonne writes, “these words increased my joy,” and it was good that they did. For Alphonse Ratisbonne would have much to suffer.

Ratisbonne tried to convince his fiancée, Flore, of the truth of what he experienced. Flore had been a deist up to that time, but before his eyes she became an atheist, a blow that stabbed him deep in the heart. He never stopped praying for her salvation, to the end of his life.

Up to the time of Ratisbonne’s conversion, his uncle treated him as though he was his only son, lavishing on him anything he wanted, and giving him a partnership in the bank he managed. After Ratisbonne’s conversion, his uncle disinherited him and revoked his partnership in the bank.

Ratisbonne writes, “there are few families so happy as mine: the affection that reigns among my brothers and sisters verges on idolatry; my sisters are so good, so loving and so lovely.” However, after his conversion, his family disowned him.

Alphonse Ratisbonne joined the Society of Jesus and became a priest. He stayed with the Jesuits for six years and then left the society to work with his brother, Theodore, in founding the Congregation of the Priests and Dames of Sion, which was devoted to serving the Jews. Alphonse Ratisbonne established three foundations in Jerusalem, which built and maintained a church, two orphanages for girls, an orphanage for boys, and a school for mechanical arts. He and the companions he gathered around him worked tirelessly for the conversion of the Jews and Muslims.

Despite his suffering, he remained always merry and kind to the end of his days, communicating his joy infectiously among those who surrounded him.

Alphonse Ratisbonne died in the Month of Mary, on May 6, 1884. His joyful last words were, “All my wishes have been granted!” At eight o’clock that evening, as he lay resting, a visible light appeared out of nowhere and shone down on his face. He opened his eyes. Those who watched him said that his eyes “seemed full of life, and they expressed at first surprise and then delight.”

He remained in ecstasy for three minutes. Much speculation followed that the Virgin Mary had appeared to him once again, and that he died gazing upon her countenance.

Bibliography

- Fr. Dirvin, Joseph I., C.M. Saint Catherine Laboure of the Miraculous Medal. Tan Book Publishers, Inc. Rockford, Illinois, 1958.

- Ratisbonne, Alphonse, and De Bussieres, Theodore. The Conversion of Ratisbonne. Roman Catholic Books. Fort Collins, CO, 2000.

- http://www.notredamedesion.org/en/page.php?id=3&T=1

- http://www.marypages.com/ratisbonneEng1.htm

- http://www.miraclesofthechurch.com/2010/11/miraculous-medal-apparition-of-virgin.html