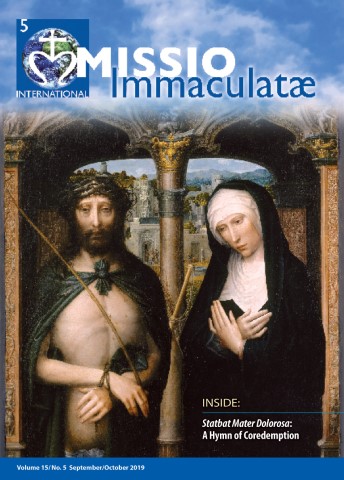

Saint Maximilian Kolbe believed the Immaculate Conception was the “Golden Thread” running throughout the history of the Franciscan Order. This article examines the claim that one could say this “Golden Thread” has shades of coredemption in it as well. We recount in brief the history of devotion to Our Lady as considered in her role, and the part which the sons of Saint Francis have played and are playing in bringing this Marian embroidery to its completion. The Stabat Mater by the Franciscan, Jacopone da Todi, clearly shows the rich development that theological reflection on the coredemption had already reached by the 13th century. One could rightly call it the “Hymn of Coredemption,” or “The Ballad of the Coredemptrix.”

Introduction

When we listen to or chant the “Stabat Mater Dolorosa,”[1] generally it is during the season of Lent and the Stations of the Cross. Although its use is limited, the “Stabat Mater”[2] has been put to music by more composers than any other text.[3]

Although we know it as a liturgical hymn, it originated as a Latin poem, penned by a little-known Franciscan friar, Jacopone da Todi, at the beginning of the 14th century. Composed of twenty verses, the “Stabat Mater” evokes the pain and grief of the Mother standing at the Foot of the Cross, offering her Son for the redemption of humanity.

How did this medieval poem make its way from the pen of this little known Franciscan Friar from Todi into the liturgy and devotion of the Universal Church? Can we not make the claim that the “Stabat Mater,” chanted by medieval flagellants, is a “Hymn of Coredemption”?

Part 1 of this article-series will introduce the historical background of the Sorrowful Mother standing at the Foot of the Cross in the life and the devotion of the Church preceding Jacopone da Todi, which was part of the foundation and inspiration that moved him as he gazed upon this mystery of our salvation. The “Stabat Mater” invites us to contemplate the Mother who suffers, the Mother who redeems, the Mother who redeems because she suffers—the Coredemptrix—and who invites us to be coredeemers with her.

History of Devotion to Our Lady’s Role in the Work of Redemption

Devotion to the Sorrowful Mother in the life of the Church began on Calvary, as described by the Evangelist, the beloved disciple, who was also present at the Foot of the Cross:

Standing by the Cross of Jesus were His mother and His mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary of Magdala. When Jesus saw His mother and the disciple there whom He loved, He said to His Mother, “Woman, behold, your son.” Then He said to the disciple, “Behold, your Mother.” And from that hour the disciple took her into his home” (Jn 19:25-27).

Over the centuries, the Church—after the example of the “beloved disciple”—has taken the last will and testament of Our Lord to heart, taking the Sorrowful Mother standing at the Foot of the Cross into her home and beholding her as the Mother of God, the Perpetual Virgin, the Immaculate Conception, assumed body and soul into heaven, and the noble associate in the work of Redemption. It seems that Our Lady’s role in the work of Redemption has been treated prophetically according to the words of Sacred Scripture, “the first shall be last,”[4] in the Church’s attainment of what is already fully realized in the Woman standing at the Foot of the Cross. What initiated the whole contemplative gaze is only now in our modern times on the verge of receiving its due recognition as the Fifth Marian Dogma. That contemplative gaze has, with time, uncovered the vast riches encompassed by this mystery.

During the first centuries of the Church, while theological debates regarding the nature of Christ were taking place, the Church Fathers also wrote about Christ’s Mother who stood at the Foot of the Cross. It is believed that she daily visited the scenes of her Son’s Passion.

In the 2nd century, St. Justin Martyr presented what we know as the “Eve-Mary parallel”: the Son of God became man through a Virgin, so that the disobedience caused by the serpent might be undone in the same way it had begun. Just as the harmful action of Eve was subordinate to that of Adam, on whom fell the responsibility for sin, in the same way the action of Mary in the order of human salvation remains absolutely subordinate to the necessary and essential action of Christ, the only Redeemer.[5]

In his writings, St. Irenaeus illustrated Mary’s role in the work of Redemption, in a well-known phrase which has developed into the devotion to Our Lady, Undoer of Knots: “The knot of Eve’s disobedience was untied by Mary’s obedience. What Eve bound through her unbelief, Mary loosed by her faith.” Thus, Mary became the cause of salvation for herself and for the whole human race.[6]

In the 4th century, Constantine legalized Christianity. With that came the marking of important “stations” along the Lord’s Via Crucis. Likewise, the Church entered more deeply into Mary’s sufferings. St. Basil the Great presented Mary as the one who remains united to Jesus as she enters into the darkest of the nights of faith, becoming the supreme model in the practice of heroic faith, fundamental to her cooperation in the Work of Redemption.[7]

In addition to writings, the 5th and 6th centuries presented images that brought the suffering of Christ to the minds of the faithful. Thus, much of the piety and devotion of the faithful at this time focused on the suffering humanity of Christ.

The first crucifix, a visual image of the Crucified Christ on the Cross, which called to mind His Passion and Death, was found in the 5th century. Also, devotion to the important “stations” along the Via Crucis grew in popularity, along with interest in “reproducing” the holy places in other areas.

About the same time, the now famous Shroud of Turin, the “Image Not Made By Hands,” was discovered in Edessa (southern Turkey);[8] it became the origin for all Byzantine and Orthodox icon images of Christ that followed. It also sparked renewed interest in the Passion of Our Lord, as it was tangible evidence of the sufferings of Our Savior. This is important because, as the Church meditated on the sufferings of Christ the Redeemer, it was led, for this very reason, to contemplate the compassionate suffering of the Mother of the Redeemer.

Later in the 6th century, we find illustrated in the Syriac Gospel the elements of the Crucifixion scene, including the thieves, the soldiers, the Virgin Mary, the holy women and St. John. The disposition of the Mother at the Foot of the Cross is portrayed with richer humanity and expression of pain.

In the 7th century, St. Ildephonsus of Toledo wrote, “Not taken by the hand of the persecutors, she stood erect at the Foot of the Cross.”[9] Again, as did St. Irenaeus in the 2nd century, the Mother was called “Cause of our Salvation” and “Repairer of the Human Race.”

Towards the end of the 7th century, the Council held at Constantinople (692) established the veneration of the Cross (Can. 73) and “that the icons of the human being, the One who has taken away the sins of the world, should be erected in the place of the ancient Lamb” (Can. 82).

In his encyclical, Ad diem illam, Pope Pius IX quotes Venerable Bede, who lived in the 8th century and who pointed out the Virgin Mother’s mission of coredemption: “It is only to the praise of the Virgin that she furnishes the material flesh of the Son of God before giving Him birth in His members, but also that she prepares and presents Him as victim on the altar for the salvation of men… this being her Mission.”[10]

Because of the emigration of Byzantine illustrators to the West at the time of the quarrel of the iconoclasts, their influence on the art of the West was seen in the Carolingian era (late 8th and 9th centuries). For example, one of the first depictions of Christ dead on the Cross is in the Utrecht Psalter (820), in the illustration for Psalm 115, showing a crucifixion with a chalice catching the blood flowing from the side of Christ.[11] To the left of Christ are the Virgin Mary and John; the Virgin is shown as a suffering maternal figure, but with a limited realism.

A 10th century hymn sung in the Swiss Monastery of Saint Gall depicts Our Lady’s coredemptive mission, giving her the title of Reparatrix, and saluting her as the “Very Mother of God and illustrious restorer of the world.” Similarly, in an 11th century manuscript from the Parisian Monastery of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the author begs Our Lady “who merited to restore the world to be the restorer of souls and bodies.”[12]

Expressions of the Mother of Sorrows and that of Her Son continued to grow in richness and depth in the 12th century. The great Marian Doctor, St. Bernard, highlighted Our Lady’s role in the Redemption and played a leading role in spreading devotion to the Mother of Sorrows. In his sermon, read in the Office of Readings for the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows, St. Bernard describes the martyrdom of the Virgin at the Foot of the Cross. Mary’s Heart is pierced by a sword when Her Son’s Body is pierced by nails and the spear: “He died in body through a love greater than anyone had known. She died in spirit through a love unlike any other since His.”[13]

In like manner, St. Arnold of Chartres spoke of the Virgin’s interior holocaust: “Jesus honors His Mother with such an affection that… He inclines from the height of the Cross towards [her] and speaks to her, demonstrating with this gesture what merit and what grace she enjoys alongside Him, she whom He looks upon at that moment with His Head pierced and His hands and feet perforated, as He prepares Himself to breathe His last. The affection of His Mother touches Him, since in that moment there is only one will in Christ and Mary, and it is the same holocaust that the two offer together: she in the blood of her heart, He in the blood of His flesh.”[14]

Also in the 12th century, we see images emerging like that of the San Damiano Crucifix (around 1187),[15] an icon of Eastern origin or style, which also portrays Our Lady at the Foot of the Cross and Blood flowing from Christ’s wounded side. The style of the San Damiano Crucifix was popular at the time and served to teach the meaning of the event depicted, and to strengthen the faith of the people.[16] For at this time, and into the 13th century, the faith of the people had grown cold. It was this San Damiano Crucifix that captured the heart of St. Francis of Assisi, who heard the voice of the Lord say to him: “My Church is in ruins … go, rebuild My Church.”

Francis’ heart burned with deep love for Jesus Crucified and Our Lady. Zealous to do as the Lord Jesus charged him, at the heart of the charism and life of Francis and of the Franciscan Order was the rebuilding of the Church. In his writings, Francis’ devotion to the Passion of Christ and to the Compassionate Mother is evident. For example, in the Office of the Passion, Francis inserted an Antiphon to Our Lady, which shows that meditation on the Passion must include the Holy Virgin who stood at the Foot of the Cross:

Holy Virgin Mary, among women,

there is no one like you born

into the world:you are the daughter and the

servant of themost high and supreme King

and Father of Heaven,you are the mother of our most holy Lord Jesus Christ,

you are the spouse of the

Holy Spirit.Pray for us with Saint Michael

the Archangeland all the powers of the heavens and all the saints

to your most holy beloved Son,

the Lord and Master.[17]

Two years before he died, Francis received the Stigmata in his hands, feet, and side (the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, 1224). St. Bonaventure, who would one day follow in his footsteps by becoming Minister General of the Order, tells us that “Francis rejoiced because of the gracious way Christ looked upon him under the appearance of the Seraph, but the fact that He was fastened to a cross pierced his soul with a sword of compassionate sorrow.”[18] His portrayal calls to mind Our Lady’s own Heart pierced with a sword as foretold by Simeon (cf. Lk 2:34-35).

Francis became a “living crucifix,” another Christ, which again put before the hearts and minds of the faithful the Passion of the Redeemer and the self-emptying love of God for His creatures. As he never ceased to contemplate this marvelous mystery and to desire to be conformed to the Cross of Jesus Christ in every way, so he encouraged the faithful to do the same.

Imitating their Seraphic Father Francis’ overflowing love for our Crucified Lord, His Mother, and Holy Mother Church, the Franciscan brothers went forth beyond Assisi to make the Gospel of Christ tangible for the people, as Francis did with the Nativity scene at Greccio. The new spirituality of the Franciscans, whose founder was the first to bear visibly the wounds of Christ on his body, spread wherever the Franciscans went. Poems, hymns, and plays stirred the hearts of the people.

Of particular interest is the contribution of Franciscan spirituality to the development of medieval theater in England. In 1224, St. Francis sent a group of his friars to England; by 1240 there were thirty-four communities of Friars Minor. The first contact of the friars with the English theater took place by order of Bishop Robert Grosseteste of Lincoln, who was concerned about the irreverence of contemporary religious dramas. He encouraged the Franciscans to take charge of them. Thus, Franciscan spirituality made a fundamental contribution to the aesthetics of medieval England of the 13th and 14th centuries, especially in the fields of art, lyric, and drama. The early religious dramatic activity in England developed in large measure within the background of the Franciscan spirituality of joy, song, and the drama of St. Francis.[19]

The profound interest in the sufferings of Christ and the emotions which meditation upon them provoked are found in the writings of St. Bonaventure, in which he invites the faithful to recall the Passion of Christ and to engage in fervent and demanding contemplation of both the suffering Christ and the sufferings of Mary.

The focus of the mystical reflections of St. Bonaventure, the “Seraphic Doctor,” was the life and Passion of Jesus. For him, the sufferings of the Redeemer upon the Cross constitute “the center of all man’s hope of salvation.”

[Mary’s] is the price through which we can gain the Kingdom of Heaven. That is to say, it is hers; taken from her, paid through her, and possessed by her. It is taken from her in the Incarnation of the Word; it is paid through her in the Redemption of the human race; and it is possessed by her in the attainment of the glory of paradise. She brought forth the price; she paid it; and she possessed it.[20]

Just as [Adam and Eve] were destroyers of the human race, so [Christ and Mary] restored it.[21]

Along with the contribution of the newly-founded Franciscan Order to the development of devotion to the Passion of Christ and the Sorrowful Mother, the Servite Order, founded in 1233 by seven young men in Tuscany, Italy, chose the Sorrows of Mary as their principal devotion. This gave additional impetus to the flowering of devotion to the Sorrows of Our Lady in the Church.

Within this flowering of devotion to the Passion and Death of Jesus, and especially to the Sorrows and Compassion of Our Lady, the ground was made fertile for the writing of a “Stabat Mater” of her who was present on Calvary to utter her Fiat in the sacrificial offering of her Son on the altar of the Cross.

Conclusion of Part 1

As we have highlighted above, the history of devotion to the Sorrowful Mother in the tradition of the Church puts before us the “key image” of the “Mother Standing” in the sacred arts, poetry, sacred writings, devotions and hymns.

This history of devotion nurtured the life and spiritual formation of the little-known Italian Franciscan poet, Jacopone, the author of the “Stabat Mater,” whom we will meet next time. In the next article of this series, we will ponder the literal English translation of the Latin, in order to enter into the scene and the prayer of Jacopone’s heart, that we may join him and our Sorrowful Mother at the Foot of the Cross.

[1] There is also the “Stabat Mater Speciosa,” which focuses on the Nativity. To be clear as to which Stabat Mater is being focused on in this paper, I begin with “Stabat Mater Dolorosa.”

[2] In this article, going forward, we use “Stabat Mater.”

[3] James McMillan, https://www.spectator.co.uk/2016/10/why-are-so-many-composers-drawn-to-the-stabat-mater. Accessed July 5, 2019.

[4] Mt 20:16.

[5] Gambero, Luigi. Mary and the Fathers of the Church: The Blessed Virgin Mary in Patristic Thought (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1999), p. 47.

[6] Ibid., p. 54.

[7] Mother Abbess Elizabeth Marie Keeler, O.S.B. “The Mystery of Our Lady’s Cooperation in our Redemption as seen in the Fathers of Benedictine Monasticism from the VI to the XII century,” Mary at the Foot of the Cross – III: Mater Unitatis, Acts of the Third International Symposium on Marian Coredemption (New Bedford, MA: Academy of the Immaculate, 2003), p. 261.

[8] https://shroudencounter.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/WebFact-Sheet-Revised-2014.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2019.

[9] Keeler, p. 271.

[10] http://w2.vatican.va/content/pius-x/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-x_enc_02021904_ad-diem-illum-laetissimum.html, par. 12. Accessed July 21, 2019.

[11] Elizabeth Saxton, “Eucharist and Romanesque Art,” in A Companion to the Eucharist in the Middle Ages, ed. I. Levy, G. Macy and K. Van Ausdall (Boston: Brill, 2012), pp. 266-267.

[12] Msgr. Arthur Calkins, “The Immaculate Heart of Mary in the Theology of Reparation.” http://www.christendom-awake.org/pages/calkins/IHMTheoRep.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2019.

[13] http://www.catolico.org/_ENG/mary/martyrdom_mary.html. Accessed July 22, 2019.

[14] Keeler, p. 290.

[15] Johannes Schneider, O.F.M., Virgo Ecclesia Facta: The Presence of Mary in the Crucifix of San Damiano and in the Office of the Passion of St. Francis of Assisi (New Bedford: Academy of the Immaculate, 2004), p. 8.

[16] Fr. George Corrigan, O.F.M., https://franciscanmissionservice.org/2012/10/san-damiano-cross-telling-the-history-of-christs-passion. Accessed July 23, 2019.

[17] The Writings of St. Francis of Assisi, tr. by Paschal Robinson, https://www.sacred-texts.com/chr/wosf/wosf23.htm. Accessed July 26, 2019.

[18] Jack Wintz, O.F.M., https://www.franciscanmedia.org/fiery-seraph-wings-a-meditation-on-francis. Accessed July 21, 2019.

[19] Sandro Sticca, trans. Joseph R. Berrigan. The Planctus Mariae in the Dramatic Tradition of the Middle Ages, The University of Georgia Press, p. 14.

[20] Collations on the Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit, Conference VI: Second Conference on Fortitude (St. Bonaventure, N.Y.: Franciscan Institute: 2008), p. 124.

[21] Sermon III on the Assumption, Opera Omnia, v. 9.